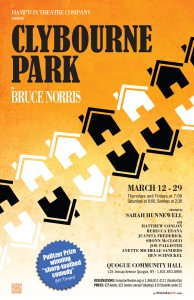

Clybourne Park

by Bruce Norris directed by Sarah Hunnewell

March 12 – 29, 2015

Bruce Norris’s Pulitzer and Tony Award-winning “sharp-toothed comedy of American uneasiness” (New York Times) that spins off Lorraine Hansberry’s “A Raisin in the Sun” to take on the taboo subject of race in the 1950s and today.CAST: Russ/Dan – MATTHEW CONLON Bev/Kathy – ANETTE MICHELLE SANDERS Francine/Lena – JUANITA FREDERICK Jim/Tom/Kenneth – BEN SCHNICKEL Albert/Kevin – SHONN McCLOUD Karl/Steve – JOE PALLISTER Betsy/Lindsey – REBECCA EDANA

MATTHEW CONLON (Russ/Dan) is grateful to return to the HTC, where he appeared most recently as Elwood P. Dowd in Harvey and as the title character in The Foreigner. He also appeared in The Heiress, The Real Thing and The Crucible some time back. NYC: HB Playwrights: The Game of Love and Death (with Herbert Berghof), Lady With a Lapdog, Freud’s Last Session (with Fritz Weaver), The Play’s the Thing and The Chase; Beckett: Judgement; Sonnet Rep: The Tempest; EST: The Traveling Lady; La Mama: A Human Equation; Tribeca Lab: The Swan; Lark: Bromius Beaujolais and God, Sex and Blue Water. Regional: Penobscot: To Kill a Mockingbird; Bay Street: Men’s Lives; Cleveland Play House: The Importance of Being Earnest; O’Neill: Fuddy Meers. Stage West: Suddenly Last Summer (with Kim Hunter); Ivoryton: Prelude to a Kiss, Bell, Book and Candle and On Golden Pond; Mendelssohn: Oedipus Rex, The Daughter-in-Law; Power Center: Waiting for Godot; Bearsville: The Lisbon Traviata. Recent Film: Sweet Lorraine; The Crimson Mask; Man From The City. TV: Law and Order(s). During the final year of ABC’s One Life to Live, Matthew played M. Claude Calmar.

REBECCA EDANA (Betsy/Lindsey) made her Hampton Theatre Company debut as Jan in Bedroom Farce and played Maddie in Desperate Affection. She has also appeared on the East End as Fraulein Kost in Center Stage’s Cabaret. She has been in numerous independent films including Greetings From Bushwick, as well as theater productions and improv troupes. Her favorite shows include Talk Radio, Happy Hour and Sweet Charity. She would like to thank her family for their tireless support and endless encouragement.

JUANITA FREDERICK (Francine/Lena), a native of Columbia, South Carolina, received her BA in Theatre and Film and a minor in Spanish from St. Augustine’s College. Some credits include: Negro Ensemble Company, Inc. Reading Series, Last of the Line as Lula and Anna Bradley; Our Town at Arden Theatre Company; and Freedom Theatre’s Journey of a Gun as the voice of the gun and Mrs. Reynolds. Juanita would like to thank God and her loving parents.

SHONN MCCLOUD (Albert/Kevin) is thrilled to be making his Hampton Theater Company debut. He was most recently seen with the Hampstead Players in A Christmas Carol (Scrooge/Fred) and Oliver Twist (Bumble/Fagin). Other regional credits include: The Liar (Alcippe), One Man, Two Guvnors (Lloyd), Oklahoma! (Judd), Ragtime (Coalhouse), Side Show (Jake), and You Can’t Take it With You (Tony). A native of Florida, he appeared in Orlando Shakespeare’s production of The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, Mad Cow Theatre’s production of Dreamgirls, and received a B.F.A. in Musical Theatre from the University of Central Florida. He would like to thank his family and friends for their continued love and support. shonnmccloud.com

JOE PALLISTER (Karl/Steve, Graphic Design) has appeared with the Hampton Theatre Company in God of Carnage (Michael Novak), The Foreigner (Rev. David Marshall Lee), The Drawer Boy (Morgan), Other People’s Money (Coles), Good People (Mike Dillon), One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (McMurphy), Doubt (Father Flynn), A Streetcar Named Desire (Stanley), Summer and Smoke (John Buchanan Jr.) and Lobby Hero (Bill). Other local work includes Bay Street’s productions of To Kill a Mockingbird (Bob Ewell) and The Diary of Anne Frank (Mr. Kraler), The Cripple of Inishmaan (Babbybobby) at Guild Hall and Of Mice and Men (George), True West (Lee) and Twelve Angry Men (Juror #8) with Southampton’s Center Stage. Film roles include Steve in Refuge and Hunter in Dark Was The Night and the feature film A Cry From Within starring Cathy Moriarty. Other credits include recurring roles on both One Life to Live and Guiding Light. He has also appeared in several mildly humiliating skits on Late Night With Conan O’Brien. joepallister.com

ANETTE MICHELLE SANDERS (Bev/Kathy) is delighted to be making her debut with the HTC. She most recently appeared in New York in Dr. Seuss’ How The Grinch Stole Christmas at Madison Square Garden and, while she very much enjoys being a Who, is excited to be playing a human for a while! Favorite roles include Mariette in Neil Simon’s The Dinner Party (original cast with John Ritter and Henry Winkler) at the Mark Taper Forum and the Kennedy Center, Rosie (u/s) in the first national tour of Mamma Mia! and both Auntie and Mama Who in Grinch on both coasts. Regionally, Anette has recently appeared as Susu in the world premiere of Jon Marans’ A Raw Space, M’Lynn in Steel Magnolias, the Beggar Woman in Sweeney Todd (with Amanda McBroom), the Wicked Witch in The Wizard of Oz, Goneril in King Lear, and Elaine in three different productions of Simon’s Last of the Red Hot Lovers. Everybody needs a niche! Many thanks to Sarah for inviting me into the HTC family. Proud member of Actors’ Equity since 1996.

BEN SCHNICKEL (Jim/Tom/Kenneth) played Ellard in HTC’s production of The Foreigner last spring as well as Miles in The Drawer Boy, Chris Foster in Becky’s New Car and Jason in Rabbit Hole. He is a New York-based actor whose credits there include When You Comin’ Back, Red Ryder?, Rabbit Hole, Six Degrees of Separation, Billy Witch, The Dreamer Examines His Pillow, Rent, A.R. Gurney’s What I Did Last Summer, Bekah Brunstetter’s Space and the world premiere of An Appeal to the Woman of the House. A native of Minneapolis, he has also performed there at the Guthrie Theater and the Children’s Theatre Company. He received his B.F.A. in Acting from Ithaca College.

BRUCE NORRIS (Playwright) is the author, most recently, of Domesticated, which premiered at Lincoln Center in November 2013. Earlier in 2013 the Royal Court premiered The Low Road in London. Clybourne Park won the Tony Award for Best Play in 2012, the Olivier and Evening Standard Awards (London) for Best Play in 2011 and the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 2011. Other plays include The Infidel (2000), Purple Heart (2002), We All Went Down to Amsterdam (2003), The Pain and the Itch (2004), The Unmentionables (2006) and A Parallelogram (2010), all of which had their premieres at Steppenwolf Theatre in Chicago. He is the recipient of the Steinberg Playwright Award (2009) and The Whiting Foundation Prize for Drama (2006) as well as two Joseph Jefferson Awards (Chicago) for Best New Work. As an actor he can be seen in the films A Civil Action, The Sixth Sense and All Good Things. He lives in New York.

SARAH HUNNEWELL (Director) has directed many shows for the Hampton Theatre Company; favorites include Time Stands Still, The Drawer Boy, Rabbit Hole, The Enchanted April, One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, The Oldest Living Graduate, Fuddy Meers, Summer and Smoke, The Rainmaker and The Foreigner. She is also the Jill-of-all-trades otherwise known as the Executive Director of the HTC. Many thanks to her excellent cast and crew for their hard work on this production and to our audience members, patrons and all the people who help make our work possible.

PETER-TOLIN BAKER (Set Designer) is the founder and principal designer of NYC based P-T B Design Services and, as such, provides creative visual design solutions for a range of retail brands, exhibitions and promotional events. Previously, he was the Vice President of Visual Merchandising at Tiffany & Co. and the visual manager with the legendary luxury emporium Henri Bendel. Additional design experience, in California, includes clothing design for Japanese Weekend and design and construction for E.M. Fabrications, a custom display and prop company. Baker was also both production designer and performer with the groundbreaking band Voice Farm. Throughout his career Baker has continued to work as scenic designer for dozens of dramatic and musical productions, including local HITFest’s recent productions of In the Next Room or the vibrator play, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and In The Bar of a Tokyo Hotel. Clybourne Park marks his debut with the Hampton Theatre Company.

SEBASTIAN PACZYNSKI (Lighting Designer) first worked with the Hampton Theatre Company when he designed the company’s 2003 production of Summer and Smoke at Guild Hall in East Hampton and has designed all the company’s productions since Proof in 2004 as well as the theater’s new lighting system. He has designed lighting for theater, dance and special events in a number of Broadway, Off Broadway, Off Off Broadway and regional venues. He has also worked in film and television as the director of photography. He has designed numerous productions for Guild Hall and for the Hamptons Shakespeare Festival.

TERESA LEBRUN (Costume Designer) is the resident costumer for the Hampton Theatre Company and has designed costumes for all the company’s recent productions. Teresa has also costumed for Spindletop Productions at Guild Hall. Much love to her boys Josh and Noah.

DIANA MARBURY (Set Decor & Properties) has dressed and “propped” many a set over the company’s 30-year history, working hand in hand with the HTC’s talented set designers. She and all the company members are incredibly grateful to all the local businesses and individuals who lend furniture and props for our productions. Also, a big hand to our wonderful patrons, who continue to give their support, in spite of these tough financial times. We hope you are enjoying our 30th Anniversary season!

JOHN ZALESKI (Stage Manager). This is John’s 33rd Production with HTC. Thank you, Catherine, for your love, patience, and support on this, the 120th Opening Night. Always in my Wings…

CHRISSIE DEPIERRO (Assistant Stage Manager) is excited to return for her second season as the Hampton Theatre Company celebrates its 30th Anniversary. Thrilled to be a part of such a wonderful and talented group of people who make the productions come alive. Hats off to my fellow “Techies” who make the magic happen. Love always to my three shining stars who always support me, Matthew, Kristopher and Theresa.

ROB (MARYAM) DOWLING (Lighting & Sound Technician) has done lighting and sound for 22 years with various theater groups on the East End. Rob has also helped Sebastian with lighting setup at Guild Hall, the Ross School, and other local venues. This is Rob’s seventh season with the Hampton Theatre Company and he is very happy to be part of the show and the company.

REBECCA EDANA (Betsy/Lindsey) made her Hampton Theatre Company debut as Jan in Bedroom Farce and played Maddie in Desperate Affection. She has also appeared on the East End as Fraulein Kost in Center Stage’s Cabaret. She has been in numerous independent films including Greetings From Bushwick, as well as theater productions and improv troupes. Her favorite shows include Talk Radio, Happy Hour and Sweet Charity. She would like to thank her family for their tireless support and endless encouragement.

JUANITA FREDERICK (Francine/Lena), a native of Columbia, South Carolina, received her BA in Theatre and Film and a minor in Spanish from St. Augustine’s College. Some credits include: Negro Ensemble Company, Inc. Reading Series, Last of the Line as Lula and Anna Bradley; Our Town at Arden Theatre Company; and Freedom Theatre’s Journey of a Gun as the voice of the gun and Mrs. Reynolds. Juanita would like to thank God and her loving parents.

SHONN MCCLOUD (Albert/Kevin) is thrilled to be making his Hampton Theater Company debut. He was most recently seen with the Hampstead Players in A Christmas Carol (Scrooge/Fred) and Oliver Twist (Bumble/Fagin). Other regional credits include: The Liar (Alcippe), One Man, Two Guvnors (Lloyd), Oklahoma! (Judd), Ragtime (Coalhouse), Side Show (Jake), and You Can’t Take it With You (Tony). A native of Florida, he appeared in Orlando Shakespeare’s production of The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, Mad Cow Theatre’s production of Dreamgirls, and received a B.F.A. in Musical Theatre from the University of Central Florida. He would like to thank his family and friends for their continued love and support. shonnmccloud.com

JOE PALLISTER (Karl/Steve, Graphic Design) has appeared with the Hampton Theatre Company in God of Carnage (Michael Novak), The Foreigner (Rev. David Marshall Lee), The Drawer Boy (Morgan), Other People’s Money (Coles), Good People (Mike Dillon), One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (McMurphy), Doubt (Father Flynn), A Streetcar Named Desire (Stanley), Summer and Smoke (John Buchanan Jr.) and Lobby Hero (Bill). Other local work includes Bay Street’s productions of To Kill a Mockingbird (Bob Ewell) and The Diary of Anne Frank (Mr. Kraler), The Cripple of Inishmaan (Babbybobby) at Guild Hall and Of Mice and Men (George), True West (Lee) and Twelve Angry Men (Juror #8) with Southampton’s Center Stage. Film roles include Steve in Refuge and Hunter in Dark Was The Night and the feature film A Cry From Within starring Cathy Moriarty. Other credits include recurring roles on both One Life to Live and Guiding Light. He has also appeared in several mildly humiliating skits on Late Night With Conan O’Brien. joepallister.com

ANETTE MICHELLE SANDERS (Bev/Kathy) is delighted to be making her debut with the HTC. She most recently appeared in New York in Dr. Seuss’ How The Grinch Stole Christmas at Madison Square Garden and, while she very much enjoys being a Who, is excited to be playing a human for a while! Favorite roles include Mariette in Neil Simon’s The Dinner Party (original cast with John Ritter and Henry Winkler) at the Mark Taper Forum and the Kennedy Center, Rosie (u/s) in the first national tour of Mamma Mia! and both Auntie and Mama Who in Grinch on both coasts. Regionally, Anette has recently appeared as Susu in the world premiere of Jon Marans’ A Raw Space, M’Lynn in Steel Magnolias, the Beggar Woman in Sweeney Todd (with Amanda McBroom), the Wicked Witch in The Wizard of Oz, Goneril in King Lear, and Elaine in three different productions of Simon’s Last of the Red Hot Lovers. Everybody needs a niche! Many thanks to Sarah for inviting me into the HTC family. Proud member of Actors’ Equity since 1996.

BEN SCHNICKEL (Jim/Tom/Kenneth) played Ellard in HTC’s production of The Foreigner last spring as well as Miles in The Drawer Boy, Chris Foster in Becky’s New Car and Jason in Rabbit Hole. He is a New York-based actor whose credits there include When You Comin’ Back, Red Ryder?, Rabbit Hole, Six Degrees of Separation, Billy Witch, The Dreamer Examines His Pillow, Rent, A.R. Gurney’s What I Did Last Summer, Bekah Brunstetter’s Space and the world premiere of An Appeal to the Woman of the House. A native of Minneapolis, he has also performed there at the Guthrie Theater and the Children’s Theatre Company. He received his B.F.A. in Acting from Ithaca College.

BRUCE NORRIS (Playwright) is the author, most recently, of Domesticated, which premiered at Lincoln Center in November 2013. Earlier in 2013 the Royal Court premiered The Low Road in London. Clybourne Park won the Tony Award for Best Play in 2012, the Olivier and Evening Standard Awards (London) for Best Play in 2011 and the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 2011. Other plays include The Infidel (2000), Purple Heart (2002), We All Went Down to Amsterdam (2003), The Pain and the Itch (2004), The Unmentionables (2006) and A Parallelogram (2010), all of which had their premieres at Steppenwolf Theatre in Chicago. He is the recipient of the Steinberg Playwright Award (2009) and The Whiting Foundation Prize for Drama (2006) as well as two Joseph Jefferson Awards (Chicago) for Best New Work. As an actor he can be seen in the films A Civil Action, The Sixth Sense and All Good Things. He lives in New York.

SARAH HUNNEWELL (Director) has directed many shows for the Hampton Theatre Company; favorites include Time Stands Still, The Drawer Boy, Rabbit Hole, The Enchanted April, One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, The Oldest Living Graduate, Fuddy Meers, Summer and Smoke, The Rainmaker and The Foreigner. She is also the Jill-of-all-trades otherwise known as the Executive Director of the HTC. Many thanks to her excellent cast and crew for their hard work on this production and to our audience members, patrons and all the people who help make our work possible.

PETER-TOLIN BAKER (Set Designer) is the founder and principal designer of NYC based P-T B Design Services and, as such, provides creative visual design solutions for a range of retail brands, exhibitions and promotional events. Previously, he was the Vice President of Visual Merchandising at Tiffany & Co. and the visual manager with the legendary luxury emporium Henri Bendel. Additional design experience, in California, includes clothing design for Japanese Weekend and design and construction for E.M. Fabrications, a custom display and prop company. Baker was also both production designer and performer with the groundbreaking band Voice Farm. Throughout his career Baker has continued to work as scenic designer for dozens of dramatic and musical productions, including local HITFest’s recent productions of In the Next Room or the vibrator play, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and In The Bar of a Tokyo Hotel. Clybourne Park marks his debut with the Hampton Theatre Company.

SEBASTIAN PACZYNSKI (Lighting Designer) first worked with the Hampton Theatre Company when he designed the company’s 2003 production of Summer and Smoke at Guild Hall in East Hampton and has designed all the company’s productions since Proof in 2004 as well as the theater’s new lighting system. He has designed lighting for theater, dance and special events in a number of Broadway, Off Broadway, Off Off Broadway and regional venues. He has also worked in film and television as the director of photography. He has designed numerous productions for Guild Hall and for the Hamptons Shakespeare Festival.

TERESA LEBRUN (Costume Designer) is the resident costumer for the Hampton Theatre Company and has designed costumes for all the company’s recent productions. Teresa has also costumed for Spindletop Productions at Guild Hall. Much love to her boys Josh and Noah.

DIANA MARBURY (Set Decor & Properties) has dressed and “propped” many a set over the company’s 30-year history, working hand in hand with the HTC’s talented set designers. She and all the company members are incredibly grateful to all the local businesses and individuals who lend furniture and props for our productions. Also, a big hand to our wonderful patrons, who continue to give their support, in spite of these tough financial times. We hope you are enjoying our 30th Anniversary season!

JOHN ZALESKI (Stage Manager). This is John’s 33rd Production with HTC. Thank you, Catherine, for your love, patience, and support on this, the 120th Opening Night. Always in my Wings…

CHRISSIE DEPIERRO (Assistant Stage Manager) is excited to return for her second season as the Hampton Theatre Company celebrates its 30th Anniversary. Thrilled to be a part of such a wonderful and talented group of people who make the productions come alive. Hats off to my fellow “Techies” who make the magic happen. Love always to my three shining stars who always support me, Matthew, Kristopher and Theresa.

ROB (MARYAM) DOWLING (Lighting & Sound Technician) has done lighting and sound for 22 years with various theater groups on the East End. Rob has also helped Sebastian with lighting setup at Guild Hall, the Ross School, and other local venues. This is Rob’s seventh season with the Hampton Theatre Company and he is very happy to be part of the show and the company.

Director – SARAH HUNNEWELL Assistant Director – JAMES EWING

Set Design – PETER-TOLIN BAKER

Lighting Design – SEBASTIAN PACZYNSKI

Costume Design – TERESA LEBRUN

Set Decor & Properties – DIANA MARBURY

Stage Manager – JOHN ZALESKI

Assistant Stage Manager – CHRISSIE DEPIERRO

Backstage Crew – ROBERT ARCHER

Set Design – PETER-TOLIN BAKER

Lighting Design – SEBASTIAN PACZYNSKI

Costume Design – TERESA LEBRUN

Set Decor & Properties – DIANA MARBURY

Stage Manager – JOHN ZALESKI

Assistant Stage Manager – CHRISSIE DEPIERRO

Backstage Crew – ROBERT ARCHER

Set Construction – PETER-TOLIN BAKER, TONY CINQUE, MATTHEW CONLON, JAMES EWING,

DEMETRIUS FUIAXIS, SEAN MARBURY, SEAMUS NAUGHTON, VINCENT RASULO

Sound Design – SARAH HUNNEWELL, JAMES EWING

Lighting/Sound Tech – ROB DOWLING, SEAMUS NAUGHTON

Production Graphics – JOE PALLISTER

Program, Publicity & Box Office – SARAH HUNNEWELL

House Manager – JULIA MORGAN ABRAMS

Advertising Sales – SARAH HUNNEWELL, LUCINDA MORRISEY

Production Photographer – TOM KOCHIE

Sound Design – SARAH HUNNEWELL, JAMES EWING

Lighting/Sound Tech – ROB DOWLING, SEAMUS NAUGHTON

Production Graphics – JOE PALLISTER

Program, Publicity & Box Office – SARAH HUNNEWELL

House Manager – JULIA MORGAN ABRAMS

Advertising Sales – SARAH HUNNEWELL, LUCINDA MORRISEY

Production Photographer – TOM KOCHIE

‘CLYBOURNE PARK’ REVIEW: RACIAL FIREWORKS IN QUOGUE

By STEVE PARKS Newsday ‘Clybourne Park” exposes what we euphemistically call “demographic changes” from the early civil rights movement (1959) to the inauguration of the first African-American president (2009). It’s astonishing how funny — and profane — such a journey can be.Bruce Norris’ Pulitzer- and Tony-winning 2011 play revisits the house that the black family in Lorraine Hansberry’s “A Raisin in the Sun” moved into at the end of her revelatory 1959 play, based on her family’s experience of buying a house in a previously all-white Chicago neighborhood. That sale was the subject of a 1940 lawsuit. The house was designated a historic landmark in 2010.

In “Clybourne Park,” directed with an unerring vernacular ear by Hampton Theatre Company’s Sarah Hunnewell, that house is about to be rebuilt in grand style by a yuppie couple who consider themselves urban pioneers, reintegrating a “ghetto” neighborhood.

In Act I, we learn why the home became affordable to the Younger family, whom we never see in “Clybourne Park.” The lone crossover character from “Raisin” is Karl, who’s just come from a futile attempt to dissuade the Youngers from moving in. He’s arrived with his pregnant, deaf wife Betsy to talk the white homeowners, Russ and Bev, into reneging on the contract. Joe Pallister’s Karl skittishly skirts hate language, but his character’s subtext is nakedly racist. Matthew Conlon as Russ and Anette Michelle Sanders as Bev reflect collateral damage of a tragedy that’s lowered the asking price for their home. Rebecca Edana is convincingly clueless as hearing-impaired Betsy, while Ben Schnickel as a feckless clergyman is amusingly banal. Juanita Frederick as Francine, the black “help,” and Shonn McCloud as her husband provide rare dignity in this we’re-all-a-little-bit-racist scenario.

Act II, taking place 50 years later, turns the tables as each actor plays a new character but reflects his/her Act I persona with mirror-image repartee. (“Have you ever seen a black guy ski?” morphs into “Do white guys tap dance?” Other jokes are X-rated.) The new homeowners want to turn the property — Peter-Tolin Baker’s transformative set is itself a character — into a McMansion. Neighborhood representatives — a black couple — say it’s ostentatious. (Translation: too white.) Plans include a koi pond, which requires digging. A trunk is unearthed — revealing a secret that’s haunted the house on Clybourne Street for half a century.

Black or white, we get it.

SCATHING SATIRE ‘CLYBOURNE PARK’ EXPOSES RACIAL FAULT LINES

By Lorraine Dusky The East Hampton Press & The Southampton PressRace in America will always be a subject aware by all, but not approached by many, because “tension” is the word naturally associated with it.

Playwright Bruce Norris bites down hard and shakes around that disturbing disquiet with his volatile, scathing satire of tribal mores and manners, “Clybourne Park,” which Hampton Theatre Company opened last weekend at Quogue Community Hall. Fifty years pass from first act to the second, and by the time Mr. Norris is done, you will have laughed, yet be keenly reminded how far we have not come.

At this moment in America, the play is more relevant than ever, as nightly the news has been of black men dying at the hands of white cops and, in one case, a neighborhood vigilante. A video of Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity members at the University of Oklahoma singing a racist chant is repeated over and over again. The Department of Justice revealed white cops and city officials in Ferguson, Missouri, sent each other jokey emails celebrating bigotry.

Against this backdrop, how do the racial fault lines exposed over housing—the subject of Mr. Norris’s highly acclaimed satire—stack up?

Just fine, actually. Only when blacks and whites learn to know each other and live together will the prejudices and fears abate.

The play opens in 1959, somewhere in Chicago on Clybourne Park, where a middle-aged white couple, Russ (a superb Matthew Conlon) and Bev (Anette Michelle Sanders)—bickering, haunted, eager to move on—are packing up and moving from their longtime home, a set of beiges evoking a comfortable, cozy residence. Their “colored” maid Francine (Juanita Frederick) is, as expect, subservient.

Then, a group of helpful friends barge in: Jim (Ben Schnickel), a diffident local minister; Albert (Shonn McCloud), Francine’s unfailingly polite husband; and, most importantly, the animated Karl (Joe Pallister) and his deaf and very pregnant wife, Betsy (Rebecca Edana).

Things really come to life when Karl’s actual mission becomes apparent. As a representative of the neighborhood association, he is there to stop the sale to a Negro family with three children. There goes the neighborhood!

In a white shirt and a short tie, Mr. Pallister is pretty damn perfect and convincing as that good man who only wants what’s best for everyone, and that is a neighborhood that stays lily white.

Fast-forward 50 years. In the second act, Mr. Pallister is Steve. With his wife, Lindsey (also Ms. Edana), they are the hip white couple that wants to buy the same house from Act I, just to tear it down and build a new one that will be bigger.

They are at the same old place reviewing the renovation plans with lawyer-real estate types, portrayed by Ms. Sanders and Mr. Schnickel, and a black couple in the neighborhood, Ms. Frederick and Mr. McCloud again, who have concerns about the house being torn down and what kind of structure will replace it. In fact, what they are really concerned about is the gentrification of their solidly middle-class black neighborhood.

The conversation starts out well enough, but soon all hell breaks loose as racist jokes and cants pile up like battery charges in a war of words. The play is funny, but that kind of uncomfortable funny that hits close to the bone. People talk, or yell, and interrupt each other while mostly trying to be “nice.” Or at least what could pass as reasonable. Including any of the lines here would be offensive, and they wouldn’t be amusing to any but a bedrock bigot.

The characters are caricatures, but that is why they work so well, embodying the learned phrases, evasions and prejudices of 50 years ago—and still today in what no one really thinks of as a post-racial world, no matter how pleasant the thought might be.

Was I reminded of the fear of “white flight” that gripped the suburbs of Detroit in the 1950s and 1960s when I lived there? Oh, yes. My hometown of Dearborn, Michigan, was a famously racist hot spot.

It was the only place north of the Mason-Dixon line George Wallace campaigned during his quixotic presidential bid. It was the site of the only Freedom March in the North, which I watched from the steps of City Hall, as both reporter and supporter. It was where the longtime mayor’s campaign slogan was a racist double entendre: “Keep Dearborn Clean.”

I left in 1964 and was not sorry to go.

Director Sarah Hunnewell chose well with this play, not an obvious one for the largely white audiences of the Hamptons, even though it won the major awards in the United States—a Pulitzer and a Tony—and England, where it picked up the Laurence Olivier Award, the British equivalent of a Tony. The ensemble cast did the material justice; everyone’s excellent, bringing to life the concealed prejudices while—in the second act at least—trying to pretend they aren’t there.

The 1950s clothes and décor by Teresa LeBrun and Diana Marbury evoke the mood and times, but what’s that misplaced Gucci bag doing on the table? Bev would never have been able to afford it, and knock-offs weren’t around yet. It may be the right vintage, but it’s as noticeable as neon.

“Clybourne Park” was on Broadway the same time as “Race,” the David Mamet play I saw; I made the wrong choice. Mr. Norris’s satire will get under your skin, and stay there.

Ms. Hunnewell and the capable troupe, under her direction, amply made up for my mistake.

CLYBOURNE PARK HITS A SENSITIVE MARK

by Beth Young East End BeaconThe Hampton Theatre Company always seems to shine when given a meaty, topical play to work with, and right now, given the unraveling of race relations in the heart of the country, it doesn’t seem there could be a more relevant play for them to produce than “Clybourne Park.”

This play, which won the Pulitzer Prize for drama in 2011 and the Tony Award for Best Play in 2012, calls for a cast of seven to play 15 entirely different roles, and this cast does a stand-out job rising to the challenge under the masterful direction of HTC Executive Director Sarah Hunnewell.

The first act is set in 1959, when a black family moves into an all-white northwest Chicago neighborhood, and the second act, set in 2009, follows a white family buying the same house when the neighborhood has long been a black one.

If you’ve seen Lorraine Hansberry’s “A Raisin in the Sun,” it will prepare you for where “Clybourne Park” begins, but you don’t need to have seen “A Raisin in the Sun” to understand what is an old and very sad American story: even after all this time, black and white people still rarely live side-by-side.

“Clybourne Park” picks up the trail of “Raisin” character Karl Lindner, played by Joe Pallister as someone right out of a 1950s Rotary Club, in short sleeves and a tie, glasses and a ridiculous amount of faith in his beliefs about property values and race.

Karl Lindner is a representative of the white Chicago neighborhood who had offered to buy the black Younger family out of their real estate deal in “Raisin,” and “Clybourne Park” catches up with him as he goes back to the white family who sold the house to tell them of his offer.

In that house are a brooding husband and wife, Bev and Russ, who’ve lost their son to suicide after he returned from the Korean War.

Played by Anette Michelle Sanders and Matthew Conlon, they are both charming and disturbing in the way that people seem to have been in the 1950s — denying their feelings about their son’s death, which later erupt at the most horrible moments.

Mr. Conlon a regular face at recent productions at HTC does a particularly good study in mild-mannered midwestern vocal peculiarities and mannerisms, while reserving powerhouse rage for when he faces the subject of his son’s death.

Juanita Frederick, who plays the couple’s black maid, Francine, has oceans of emotions just beneath the surface of her terse responses to the couple’s requests as they pack to move. She knows her employers are not her friends, but she needs a job and she keeps her mouth shut, demurely refusing Bev’s attempted gift of a silver chafing dish — something not even her employer needs.

Her husband, Albert, is a sweetheart as played by Shonn McCloud, willing to lend a hand taking the couple’s son’s trunk downstairs when Karl, fresh from his time over at “A Raisin in the Sun”, rushes through the door to beg Bev and Russ to not sell their house to a black family.

HTC veteran Ben Schnickel, as their preacher friend Jim, tries to give them God’s perspective on the matter, while Karl’s pregnant, deaf wife, Betsy, played with great comic timing by Rebecca Edana, later comes inside from the hot car, adding a new level of absurdity to what is heard, what is actually said, and what is meant by the characters as they dance around their knowledge (or lack thereof) of their own racism.

A melee ensues, during most of which Francine and Albert are upstairs bringing down the trunk. When they come downstairs and end up in the middle of the mess, they stand awkwardly, almost frightened, as the white characters in the room barrage them with questions about whether they’d rather be with their own people than in a white neighborhood.

When everyone leaves, Bev begs Albert to take the chafing dish his wife has refused.

“We don’t want your things,” he says gently as Bev collapses, weeping, on the floor. “We got our own things.”

“Well, if that’s the attitude, then I just don’t know what to say anymore.” she says, “If that’s what we’re coming to.”

What does her statement mean? Well, it means exactly what it sounds like. No varnish. There is no varnish in this show that isn’t unpeeled.

Fast forward 50 years. Ms. Frederick now plays Lena, the grand-niece of the black woman who’d bought the house. She’s still quiet, but she’s far more angry. The people who bought her house, now a historic building, want to tear it down and build their dream house in its place, and her neighborhood has started a petition drive against the project.

Her husband, Kevin (Mr. McCloud), is wearing shorts and seems entirely at ease. He tells the white family that he and his wife had just returned from a vacation in Prague. He asks them if they ski. He knows that he’s blowing the white characters’ minds about how they expect black people to be, and he’s having fun with every minute of it.

Ms. Edana, still pregnant, becomes Lindsey — a hysterical helicopter mom-to-be who wants the perfect house for her baby, while Mr. Pallister, sipping a Starbucks, is recast as her husband, Steve, who can’t help but think that everything Lena and Kevin say to him is really about race. “No, we’re not questioning your ethics at all,” says Lena. “What we’re questioning is your taste.” Ms. Sanders is recast as Kathy, a complete ditz of a lawyer, who interrupts with the most absolutely inane banter possible, while Mr. Schnickel is recast as Lena and Kevin’s gay attorney, who can’t get off the phone to join the conversation.

Matthew Conlon just up and steals the show as an excavator working in the backyard who digs up the dead Korean war veteran’s truck from beneath a dead crepe myrtle tree. With sweaty dungarees, a stained t-shirt and an even more pronounced upper-midwest accent, he brings as much show-stopping ridiculousness to his character as the best of Hamlet’s gravediggers.

Peter-Tolin Baker, making his HTC debut as set designer, and set decorator Diane Marbury make good use of furniture on loan from several East End thrift shops. The scene doesn’t change from act to act, but the yellowing wallpaper and graffiti show a room that looks as if it aged 50 years over the intermission.

The details are important — in Act 2, the spackle bucket that now lives where Bev had kept the silver chafing dish says more than words ever could.

We live in a country where a black man can be president. But we don’t yet live in a country where we can honestly say we live side by side, and even be friends. There’s too much still hanging in the air between.

This production lights a candle to that volatile air. It’s a little fire in the grand scheme of things, but it matters. Go see it.

THEATER REVIEW: ‘CLYBOURNE PARK’ ENTERTAINS AS IT CHALLENGES

by Brendan J. O’Reilly Dan’s Papers“Clybourne Park,” being staged through the end of the month in Quogue, offers a comedic and provocative take on race, both during the era of the Civil Rights Movement and in modern times, when for all that’s changed, much has stayed the same.

Penned by Bruce Norris, “Clybourne Park” debuted in 2010 before moving to Broadway in 2012 for an acclaimed run. It’s clear why the play won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama, the Tony for Best Play and the Laurence Olivier Award for Best New Play, though it takes the right cast and a seasoned, deliberate director to ensure none of the humor and power of the piece is lost. Thankfully, that’s just what Hampton Theatre Company has.

Director Sarah Hunnewell found a superb cast of seven, who all must double-up on parts.

Penned by Bruce Norris, the play is a spinoff of Lorraine Hansberry’s 1959 “A Raisin in the Sun.” To enjoy and understand “Clybourne Park,” it is not necessary to have seen “A Raisin in the Sun,” but it does help to know one thing: The earlier play centers on a black family that purchases a home in a white neighborhood.

“Clybourne Park” takes place inside that home over the course of two acts separated by 50 years. The first act is set in 1959 when middle-aged couple Russ and Bev, who are still recovering from the loss of their son, are preparing to move out of their home. Without consulting Russ, Bev has asked the local clergyman to drop in on him. Adding to Russ’s frustrations, civic leader Karl Lindner—the only character who appears in both “A Raisin in the Sun” and “Clybourne Park”—storms in to try to talk the couple out of selling the house to a black family. Karl even tries to get Russ and Bev’s black housekeeper and her husband to help him make his case that it would be a bad fit.

Matthew Conlon, who was most recently seen on the Quogue stage in “Harvey” as Elwood P. Dowd, delivers another great performance. In the challenging role of Russ, he’s must be jokey, standoffish and outraged—all while masking grief just beneath the surface. Hampton Theater Company veteran Joe Pallister (“God of Carnage,” “Good People,” “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest”) is convincing as Karl, who is aggravating to Russ—and the audience—as he attempts to make his racist motivations appear benevolent. Ben Schnickel (“The Foreigner,” “The Drawer Boy”) as the well-meaning but often inept minister Pastor Jim, can really punctuate a funny exchange with his shock and facial expressions. As housekeeper Francine, Juanita Frederick is an effective “straight man” as a bystander to everyone else’s antics.

The second act is more like a second play. It’s 2009, and the cast members have taken on new roles. What ties the two acts together are the house—now rundown, like the rest of the neighborhood—and the theme of race. The roles have reversed, however. The neighborhood has become predominantly black over the past five decades, and now a white couple is moving in. Community activists fear their neighborhood is being gentrified with no regard for history.

In 1959, the house was well-kept, but cluttered with moving boxes. In 2009, it’s vandalized, with no furniture but a few crates and mixed-matched chairs. That’s all the seating that’s needed to accommodate the neighborhood association representatives, the new owners and the attorneys there to mediate. The affluent new owners want to tear down the house to make way for something bigger, and that doesn’t sit well with the neighbors.

Cellphones and side talk keep putting off the matter at hand, and the way the parties interact during casual conversation foreshadows the inevitable. Conversations on race maintain some semblance of politeness in the first act, even while the content is ugly. Come the second act, characters decide to tip-toe around race for a while, opting for thinly veiled euphemisms, before they shun political correctness and say exactly what they are feeling. It’s unsettling for the audience, because frank discussions concerning race and racism aren’t refreshing, they’re uncomfortable.<

br />

THERE GOES THE NEIGHBORHOOD, AGAIN

A work of grand historical importance by Bridget Leroy East Hampton StarTaken by themselves, either act of “Clybourne Park” — the Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award-winning dramedy by Bruce Norris now at the Hampton Theatre Company in Quogue — would stand as a searing yet comedic paean to race relations. Taken together, the two acts masterfully blend into a social commentary on the advancement (or stagnation) of black and white amalgamation over half a century in a desirable Chicago suburb.

Throw in the only white character from Lorraine Hansberry’s “Raisin in the Sun,” the first Broadway play written by an African-American woman, and you have a work of grand historical importance — and a joy to watch as well.

But if you’re expecting a comfortable ride, hang on for dear life. “Clybourne Park” is a series of remarkably awkward moments that show not only how different factions talk about themselves and each other, but also how, as a whole, they appraise the hearing-impaired, the developmentally disabled, sexual identity, men, women, pregnancy, Scandinavians, the “red Chinese,” and chafing dishes. No one emerges unscathed.

Act one takes place in 1959; the second act in 2009, both in the same house, and both with the same actors portraying immensely different roles. The first half deals with the reactions and emotional maelstrom that come when a black family buys a home in a white neighborhood. After the intermission, a lawyered-up African-American couple is trying to retain the historical significance of the house, now in a predominantly black neighborhood, as new buyers want to tear down and upzone — something those on the South Fork may have an inkling about.

The play begins with a middle-age couple, still coping with a recent tragedy, who are packing up after selling their house. Matthew Conlon and Anette Michelle Sanders play Russ and Bev with an engaging realism, whether they are simply making small talk about National Geographic or stirring up old and disturbing memories. Ben Schnickel, as Jim, the local pastor, arrives to chat — Mr. Schnickel is almost Mormonesque in his pallidity. Then Karl Lindner — that overlapping character from “Raisin” — arrives with astonishing news: the new homeowners are “colored” and he has made a counter-offer to keep them out. Joe Pallister is at his best as Karl, a man on fire with his convictions.

During all of this, Francine, the family maid, played with amazing discipline by Juanita Frederick, comes in and out of the room, packing up, asking questions, occasionally being put on the spot for her opinion but mostly ignored. Rounding out the cast are Rebecca Edana as Karl’s deaf and very pregnant wife, and Shonn McCloud, H.T.C. newcomer, who plays Francine’s husband, Albert, with a deadpan attitude in the midst of a lively debate. Even when trying to understand things from the African-American viewpoint, the Caucasian characters are reprehensibly offensive in what they consider a “progressive” way, talking about soul food as a substitute for soul. But it is in the second act when the elephant in the room becomes hysterically cringe-worthy. At least in the 1950s race was discussed; as the second act shows, Americans today will talk about virtually anything else, and almost everyone is offended by something. Ms. Edana, hearing-impaired in act one, talks almost non-stop in the second act, a white woman (still pregnant) bent on having the home she wants while trying to appease the locals to a point, as long as that point doesn’t infringe on her two-story dream. “The history of America is the history of private property,” muses her husband, Steve (Mr. Pallister). “I rather doubt that your grandparents were sold as private property,” answers Lena (Ms. Frederick), who is labeled a racist by Steve. Mr. Conlon in the second act plays the only working-class character, the small but important role of Dan, the handyman, an Irish-Catholic holdout in blackburbia who, like Francine in the first act, is basically ignored. So is it color or class? Hampton Theatre Company’s production of “Clybourne Park” is admirable in every way, from the wonderful ensemble cast, to the set by Peter-Tolin Baker, Sebastian Paczynski’s effective lighting, Teresa LeBrun’s period costumes, and Sarah Hunnewell’s masterful directing of a dialogue-driven vehicle. When Mr. Conlon’s character drags forth a buried secret at the end that unites the first and second acts, it is neglected by the other characters. Like so many who base their arguments on principle, they are too busy fighting each other to truly see the unabridged past and the scars that a war — whether fought on the battlefield or in the living room — can inflict.

Amazing…saw it opening night. Superb script; brilliant acting; funny and sad; just great!!

– SUSAN SMITH

It was terrific! We LOVED it! – PAMELA ORNSTEIN Loved, loved, loved the play last night! Just brilliant! – JOY FLYNN It was an excellent show — great acting and directing. Very enjoyable. – JUNE SCHONBERG We loved the show as did our friends. Everything about it was superb—-acting, sets, costumes. And beautifully directed. The evening flew by. Looking forward to the next show. – CAROL HAUFMAN Last Thursday night was another exciting evening of superb theatre. Every year the Hampton Theatre Company brings professional productions of the best contemporary and classic plays to the East End. Thursday’s drama, “Clybourne Park,” stretched the audience’s grasp of fifty years of America’s racial intolerance. Perfectly cast and carefully directed with humor and unease abounding, we were all treated to a night of live theatre that will keep re-entering our thoughts with the appropriate unrest the author intended. Bravo! – RICHARD BARONS It was fantastic! Telling all my friends. – DONNA SMITH We LOVED “Clybourne Park.” It was a fascinating play. The acting and directing were fantastic. Each character was two totally different people in the acts. They even looked different. – EMILY ANDREN

It was terrific! We LOVED it! – PAMELA ORNSTEIN Loved, loved, loved the play last night! Just brilliant! – JOY FLYNN It was an excellent show — great acting and directing. Very enjoyable. – JUNE SCHONBERG We loved the show as did our friends. Everything about it was superb—-acting, sets, costumes. And beautifully directed. The evening flew by. Looking forward to the next show. – CAROL HAUFMAN Last Thursday night was another exciting evening of superb theatre. Every year the Hampton Theatre Company brings professional productions of the best contemporary and classic plays to the East End. Thursday’s drama, “Clybourne Park,” stretched the audience’s grasp of fifty years of America’s racial intolerance. Perfectly cast and carefully directed with humor and unease abounding, we were all treated to a night of live theatre that will keep re-entering our thoughts with the appropriate unrest the author intended. Bravo! – RICHARD BARONS It was fantastic! Telling all my friends. – DONNA SMITH We LOVED “Clybourne Park.” It was a fascinating play. The acting and directing were fantastic. Each character was two totally different people in the acts. They even looked different. – EMILY ANDREN

Hampton Theatre Company

Hampton Theatre Company